The golden eye of Shahr-i Shokhta

The earliest evidence of humans using prosthetics are from Egypt and Iran, where prosthetics have been used for several thousand years. One of oldest archaeological findings of prosthetics is from Iran, where a woman was buried in Shahr-i Shokhta (“Burnt City”) circa 2900-2800 BCE wearing her prosthetic eye.

The prosthetic eye was made from a lightweight material, a thin layer of gold had been applied over the surface, and engraved lines radiated like rays from a central circle (representing the iris). Originally, researchers believed the lightweight material was derived from bitumen paste, but further investigation revealed a mixture of natural tar and animal fat. A tiny hole had been drilled on each side of the half-sphere (which had a diameter of 2.5 cm) to make it possible for the artificial eye to be held in place with thread.

The prosthetic eye was made from a lightweight material, a thin layer of gold had been applied over the surface, and engraved lines radiated like rays from a central circle (representing the iris). Originally, researchers believed the lightweight material was derived from bitumen paste, but further investigation revealed a mixture of natural tar and animal fat. A tiny hole had been drilled on each side of the half-sphere (which had a diameter of 2.5 cm) to make it possible for the artificial eye to be held in place with thread.

The skeleton with the artificial eye was unearthed in 2006, when an ancient necropolis in the Sistan desert was investigated by an Iranian-Italian team of archaeologists. The woman had been 182 centimetre tall, which is tall for a woman even by today´s standards and much taller than ordinary women living in the city during her lifetime. A facial reconstruction revealed that her face also differed from the norm in ancient Shahr-i Shokhta, and it is possible that she migrated there from Arabia. Seeing such a tall and unusual looking woman with one golden eye must have been something quite special for the ancient Iranians in Shahr-i Shokhta. Some scholars have theorized that she might have been a priestess and/or someone who made predictions about the future and told of otherworldly things.

Microscopical investigation confirmed that the artificial eye had indeed been worn by the woman during her lifetime; it was not something that had been added after death. The socket had a imprint from prolonged contact and marks from the thread. The woman lived circa 2900-2800 BCE and was around 25-30 years old when she died. The cause of death has not been determined.

Based on the skills of the jewellers active in Shahr-i- Shokhta at the time, the eye could have been created in that city. Covering an area over more than 150 hectares, Shahr-i- Shokhta was one of the world´s largest cities during the dawn of the urban era. The reasons for its unexpected growth and fall is still wrapped in mystery, and artefacts recovered here demonstrate a peculiar incongruity with nearby civilizations of the time. It has been speculated that Shahr-i- Shokhta might have been a civilization independent of ancient Mesopotamia.

Other early examples of prosthetics

The Egyptian big toe

The Egyptians were early pioneers of foot prosthetics, and an Egyptian mummy with an artificial big toe from circa 950-710 BCE has been found. The mummy with the artificial toe had been buried in a necropolis near ancient Thebes, and its artificial turned out to be fashioned from wood and leather. The prosthesis showed evidence of use.

In 2011, the prosthesis was reproduced by bio-mechanical engineers. They showed that this artificial toe enabled its wearer to walk in typical Egyptian sandals of the time and also barefoot.

The Hindu legend of Vishpala with the iron leg

The concept of a prosthetic leg (with supernatural connotations) is mentioned in one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts known as the Vedas. More precisely, the Rigveda (RV 1.112.10, 116.15, 117.11, 118.8 and RV 10.39.8) speaks of a woman named Vishpala who is helped in battle by the Ashvins – the Hindu twin gods of medicine, health and sciences. Vishpala loses her leg in

Khela´s battle, and the Ashvins give her a leg of iron so she can keep running. The text is dated to roughly 1200 BC. Of course, it does not infer that prosthetic legs or other artificial limbs existed in South Asia at the time; only that the idea existed.

Hegesistratus and the wooden foot (Ancient Greece legend)

Another early mentioning of a prosthetic lower limb comes from the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC). He wrote down a story about a Greek diviner named Hegesistratus, who cut off his own foot to escape from Spartan captivity. In the story, Hegesistratus uses a wooden foot as a replacement for the one he lost. Just as with the Rigveda, this story only shows us that the idea of limb prosthetics existed; it does not show if wooden artificial feet were actually used in Ancient Greece.

The artificial leg from Capua

The famous Capua leg is an artificial leg dated to 300 BCE, making it one of oldest known artificial legs. It was found in a grave in Capua, southern Italy. The limb was taken from Italy to England, where it was kept at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. An air raid destroyed the leg during World War II, but a copy of the limb exists and is kept at the Science Museum in London.

The city Capua was founded by Etruscans around 600 BCE and submitted to Rome in 338 BCE.

The Ancient Roman general Marcus Sergius and his iron hand

Marcus Sergius was a Roman general during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). When he lost his right hand during his second campaign, he had a prosthetic one made from iron to hold his shield in battle.

A (possibly embellished) description of Marcus Sergius is found in the seventh book of Pliny’s Natural History, published in AD 77:

A (possibly embellished) description of Marcus Sergius is found in the seventh book of Pliny’s Natural History, published in AD 77:

“Nobody – at least in my opinion – can rightly rank any man above Marcus Sergius, although his great-grandson Catiline shames his name. In his second campaign Sergius lost his right hand. In two campaigns he was wounded twenty-three times, with the result that he had no use in either hand or either foot: only his spirit remained intact. Although disabled, Sergius served in many subsequent campaigns. He was twice captured by Hannibal – no ordinary foe- from whom twice he escaped, although kept in chains and shackles every day for twenty months. He fought four times with only his left hand, while two horses he was riding were stabbed beneath him.

He had a right hand made of iron for him and, going into battle with this bound to his arm, raised the siege of Cremona, saved Placentia and captured twelve enemy camps in Gaul – all of which exploits were confirmed by the speech he made as praetor when his colleagues tried to debar him as infirm from the sacrifices. What piles of wreaths he would have amassed in the face of a different enemy!”

The Holy Roman Imperial Knight with an Iron Hand

The Imperial Knight (Reichsritter) Gottfried “Götz” von Berlichingen (1480 – 1562) was involved and numerous military campaigns and became known as Götz of the Iron Hand due to his use of a prosthetic hand.

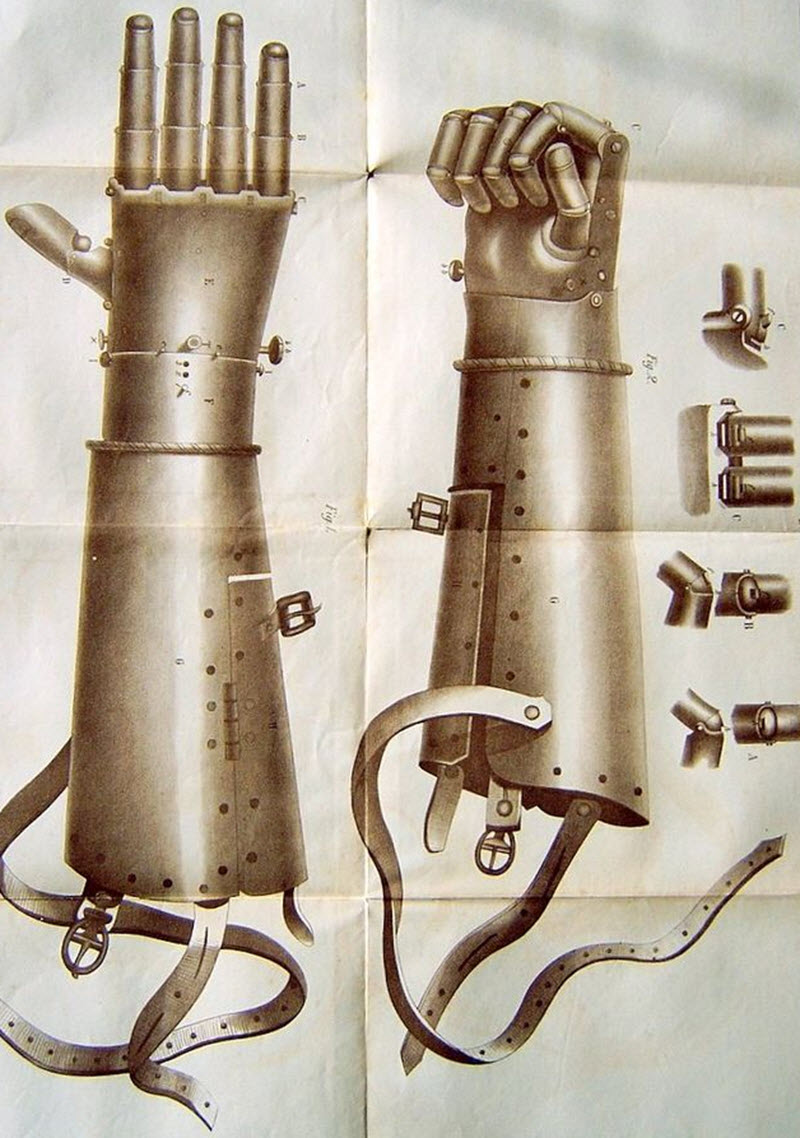

During the siege of Landshut in 1504, enemy cannon fire forced his own sword against him and he lost his right arm at the wrist. He had two mechanical replacements made: one quite simple and one considerably more advanced. Allegedly, the first one was made by a local blacksmith and a saddle maker. The second prosthesis was capable of holding objects, including military important ones such as a shield or the reins of a battle horse. Götz could therefore continue with his military pursuits even after the injury.

Both the first and the second prosthesis have been preserved and are kept at Burg Jagsthausen.

The German submarines U-59 and U-70 both bore the emblem of a “War Glove” with the legend

“Götz von Berlichingen!”, and the 2.Schnellbootgeschwader of the German Navy used the clenched Iron Fist of Götz von Berlichingen in the centre of their squadron crest.

François “Bras-de-Fer” de la Noue

The Huguenot captain François de la Noue (1531 – 1591) was known as Bras-de-Fer (Arm-of-Iron) due to his prosthetic arm. His arm had needed to be amputated after being shattered by a bullet during the siege of Fontenay in 1570, so a mechanic from La Rochelle created an iron arm for him, which included a hook designed to hold his horse´s reins. De la Noue could therefore continue his military career.

Henri de Tonti – the French explorer with a hook for a hand

Henri de Tonti (c. 1649-1704) was a French military officer and explorer, chiefly known for establishing the first permanent European settlement in the lower Mississippi valley. This settlement was named Poste de Arkansea, and eventually became the first capital of the Arkansas Territory.

Around the age 18, de Tonti joined the French military service. During the Franco-Dutch War, he was a part of a troop sent to Sicily in 1675 to support the Rebellion of Messina. While participating in military operations in the village Gesso, de Tonti lost his hand in a grenade explosion. His hand was then replaced with a metal appliance. After six months as prisoner of war, de Tonti could return to France where he continued to serve on the galleys. He wore a prosthetic hook covered by a glove, which earned him the nickname Iron Hand. After the end of the Franco-Dutch War, de Tonti became an explorer of North America.